Colab & ABC No Rio Collections

The Moore Family collection of art includes numerous works from artists who worked with the Colab artists group and the ABC No Rio art space in the Lower East Side of Manhattan in New York City.

In addition, Moore holds works which properly belong in other collections pertaining to Collaborative Projects and ABC No Rio. While there is presently no formal Colab collection outside of this grouping of materials, there is a formal ABC No Rio collection. Negotations to return the ABC No Rio material to that institution were not concluded before the artwork was moved to Milwaukee. While considerable expenses of storage and maintenance have accumulated over the years, Moore considers that he holds this material in trust for institutional deposit.

Jack Waters on the ABC No Rio Collection

Introduction:

The Moore Collection contains significant elements from two other collections – ABC No Rio and the Colab artists group. One of these exists only in my mind – the Colab collection. The other, ABC No Rio, has a substantial existence in storage spaces in New York City. I hold a rump group of works, some of which will be in the summer ‘21 exhibition at WPCA.

Jack Waters and Peter Cramer were the directors of ABC No Rio for nearly a decade. During that time, in addition to running the space, they took over the care and feeding of a collection of artworks we of the original group had started. Our idea was that when we got famous – (which, in a way, some of us did) – we could mortgage this collection to buy the building. As time went on, the collection took on a life of its own through the activities of Jack and Peter. They catalogued things, managed the storage, and most importantly produced numerous exhibitions in NYC and abroad which spotlighted the artworks and the activities of ABC No Rio itself

Jack Water’s essay, parts of which are excerpted here, was written in 2000 for a panel discussion called “The Archives of the Avant-Garde: Archiving the Unarchivable”. The panel was organized by the artist Martha Wilson of the Franklin Furnace, a very personal institution in NYC which combined artists books (a library of them), performance, and window art installations. Today Martha runs an archival center at Pratt Institute.

The Lower East Side space ABC No Rio was a poor cousin to that Tribeca institution, and an all-around oddball in the rich array of “alternative space” art institutions in NYC in the late 20th century. The problem Jack describes in the text below, of archiving the past work of the place, was much the same as that of the Franklin Furnace with its wide variety of cultural activity. In the context of an artworld fixated on individual fame and the market value of paintings and sculpture, how does a marginal resistant subcultural institution archive itself? Not only its art-making, its cultural production, but how does it preserve and represent the material traces of its struggle to survive in a politically and economically hostile climate?

That struggle isn’t over yet.

– Alan W. Moore, 2021

excerpts from

Collecting the Uncollectible, a Unique, yet Commonizing Approach

by Jack Waters, 2000

Archiving/Anarchy; Irony. The documentation of an essentially anti-materialistic expression by means of collecting and preserving the material objects produced by that ethos presents an ideological conundrum…. The intent of this paper is to address this paradox by describing the physical byproduct of a dying (if not already dead) culture of collective resistance – an archive that belies the archival norm: An historical time capsule that, with due respect and adequate attention could reveal the mechanism of a bona fide social experiment. A non-conformist mode of creation, where presentation, protest and celebration are the functional tools of social progress….

Why would a collective of individuals, whose overriding philosophy contests the very idea of “history”, and whose very existence, dedicated to the subversion of the acquisitional (read: capitalistic) logic that collecting conjures, be intrinsically engaged from the very beginning with archival concerns? ABC No Rio’s identity is largely defined by its physical location – Manhattan’s Lower East Side (Loisaida). But what is its raison d’être – the force that has made it the lone survivor of an era so glamorized by film and fiction, now that the escalation of real estate prices fostered by self perpetuated hype has sent its East Village contemporaries [i.e., other art galleries and performance spaces] the way of the dodo?

To understand No Rio’s motives for archiving is to appreciate that ABC No Rio is best defined by its activity. This is possible by examining its past, present and planned programming. The documentation of fliers, invitations, posters, publicity materials, working files, and accumulated artwork, encapsulates not only the phenomenal cultural milieu of the ‘80s, but also No Rio’s equally important ideological function as artworld gadfly. Study of these materials will show the radicalism of its common goals at inception, the externally inflicted duress, its internal contention, and the later phase of renaissance. As an art facility with international impact, a local community center, and an anarchist squat all rolled into one, No Rio is unique. Understanding ABC No Rio by way of its archives will illustrate the commonality of contemporary American art inasmuch as art has been defined as a cultural battleground, a subversive element, a political threat. It is my hope that the samples from No Rio’s past will help seal the common bonds connecting all the arts, no matter the medium or where they may be placed in the social hierarchy.

A Herstorical Overview

ABC No Rio is the by-product of a hybrid of politics and art, an action called The Real Estate Show driven by members of the organization Collaborative Projects, Inc. (Colab). The event spotlighted issues of public concern. It linked the counter-productive mismanagement of New York City to the corrupt real estate development practices of its corporate associates: Their infringement on civil rights, promoting business and profit over education, health services, substance abuse rehab, the protection of senior citizens, animal shelter, and the spiritual and aesthetic well being of the public. Art was a tool for communication, reinforced by the application of media savvy, social and political connections, pure creativity, vision, innovation and just plain chutzpa. The speculative value of the Delancey Street site that the artists, propelled by righteous indignation commandeered, was deemed too valuable to release.

The authorities compromised, offering Colab a cheaper alternative in the same vicinity. The broken down flooding fire trap was located in what had become one of NYC’s biggest drug zones, inhabited by a predominantly poor black and Latino population. That the neighborhood is the historical portal for working class immigration is poignant. The typically American trait of short memory/no history is way retail culture converts the subversive into marketable product. ‘60s radicalism was stylized as radical chic. ‘70s anti bourgeois punk origins became a style choice. Without history everything seems new and newness is equated with value. The youth driven East Village Art Boom which followed on the heels of the Times Square show was an epoch where novelty propelled a new, though short lived sector of the art market. The No Rio archives and artifacts trace the origins of this era, showing its influence on the present.

The assimilation and assessment of these materials could better contextualize the period towards a more balanced understanding of contemporary art history, addressing the neutralization of art as a communicative medium when it is presented as mere product. It is culturally important to consider the relationship between the early and current works of some of the better known artists that emerged from the Real Estate Show, and whether the current product oriented work of [ex-Colab] artists like Kiki Smith, Tom Otterness, Jenny Holzer, Judy Rifka, Jane Dickson, John Ahearn, and Mike Glier – artists who now hang in some of the very collections of the “powers that be” that the Real Estate Show (and its sister act, The Times Square Show) confronted – neutralizes their earlier, communicative, process oriented oeuvre….

There have been five overlapping generations of direction at ABC No Rio since inception. With each change of leadership there has been ideological continuity, sustained by deliberate systemic process (the formation of organizational goals and structure), and social necessity. Though the principal ideology has remained consistent, political methods, social priorities, aesthetic focus, and the overall style of the artwork has been drastically different from period to period. Yet throughout, visual art, poetry, music, performance and media have continued as on-going programmatic activities. Throughout the decade of the ‘80s ABC No Rio was an anomaly in the sphere of the “Lower East Side Art Boom”.

Cassandra-like, No Rio could be critical, yet at the same time participatory on the baseline of gentrification, a hallmark in the era of conspicuous consumption. Unlike the neighboring galleries that were its contemporaries, the deliberate absence of a No Rio sales mechanism was counter-capitalistic, yet it exhibited many of the same artists that were being hyped. Because it wasn’t dependent on earnings and had virtually no overhead, No Rio was able to sustain an exhaustive schedule of widely diverse events. A virtual who’s who of the ‘80s underground, its credibility and press cachet made it an attractive career stepping stone – a crossroads of commercial and anti-commercial art, drawing at one time or another the performances of the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company, rock stars Michelle Shocked and Beck, poet Cookie Mueller, Charles Ludlam’s Theater of the Ridiculous, the comedian Reno, poet Allen Ginsberg, and in attendance the likes of Courtney Love, Mary McFadden, Anthony Hayden Guest, and the legendary Leigh Bowery….

The early body of work archived is the exhibited material remaining there since inception. There was no formal consignment process, or systemic arrangement for pick up. The counter cultural aesthetic and the issue-specific, on-site generation of most of the work makes provenance moot. The art was not considered “property” in the usual sense….

Archive Time Line [excerpts]

• 1985- Selections from the archives are shown side by side with recent works at the anniversary exhibition, ABC No Rio, The First 5 Years at NYC Depart of Cultural Affairs’ City Gallery. [The Moore Collection contains works purchased at this show.] Works by Claes Oldenberg, Jenny Holzer, Keith Haring, and others are donated. A more formal process of acquisition is established. In addition to the visual works the archive of performance and audio documents has been augmented in film, video and tapes from the performance series component of this exhibition. Simultaneous with the City Gallery exhibition a show at Piezo Electric Gallery exhibits the ephemera. Peter and Jack, as co-directors continue as de-facto archivists. Selection is based on anthropological importance, historical value, social and political impact and subjective aesthetics….

• 1990 A more ambitious event at Kunstlerhaus in Hamburg, Germany, which exhibited the permanent collection in context with collectively produced socio-political works by 10 contemporaneous U.S. and Canadian groups.

• 1992 The board of directors incorporates No Rio implementing its autonomy. Simultaneously internal friction resulting from the recalcitrant socio-political conditions since its birth cause the board and staff to disband leaving No Rio under the management of the anarchist philosophy of the Hard Core Matinee directors. By consent of the new directorship the existing archive is maintained by Cramer, Waters and their supporters. Subsequent section of the archive is developed and expanded. Other works accumulated through the years are those left by artists exhibiting at No Rio, some by active consignment, most others simply abandoned. Approximately 100 of the works in the collection are documented, catalogued and appraised. The exact number of remaining works is still unknown.

[Since this text was written, works from the ABC No Rio collection have also been exhibited at Deitch Projects for the 25th anniversary benefit auction in 2005. The Moore Collection contains items purchased then. ABC collection works were also shown at the James Fuentes Gallery for “The Real Estate Show Revisited” exhibition in 2014. Yet again, items for the Moore Collection were purchased during this exhibition.]

The Inventory

Visual art in all mediums, video, audio and photographic documents of events including performance/conceptual works, poetry, music, media works, artist made books, and an extensive collection of zines. Ephemera including correspondence, programming notes, programs, posters, invitations, press releases, files, curators and programmer’s notes, artists slides, board documents [administrative], reviews announcements essays and press clips. One of the most important functions in archiving the so-called ephemera will be to track the historical path of political attack on the arts. The records of No Rio’s NEA grant applications and its accompanying correspondence trail will validate, in concordance with the records of similar organizational histories the “divide and conquer” methodology that preceded the overt ideological attack on government funding for the arts. NYSCA records will reveal the ironic dilemma of the funding system in which alternative institutions are placed, ie. how the process requires advance documentation of planned events, yet the funders sometimes penalize the organization’s application for lacking the spontaneity which initially interested the funder. In order to receive funding round pegs are forced into square holes, and how misfit organizations like No Rio have responded creatively within the application and reporting process.

Economics

Though its influence is international, No Rio has always existed at a grass roots level of funding. The lack of an aggressive capital drive limited substantial earned, private and foundation income. Its political commitments put it in the vanguard of the publicly defunded. Public support for the arts, as we once knew it is over. These economic factors have had a direct influence on the content and condition of its archives and visual art collection. In the beginning ABC No Rio received funding annually from two main sources of public support: the New York State Council on the Arts [NYSCA] and the National Endowment for the Arts [NEA].

[Subsequent to this writing, substantial monies were raised for a new building. Program and administrative funds, however, have remained very modest, pretty much as Jack describes them here.]

In both cases the principal contracted funds received were extremely modest organizational grants for No Rio’s Visual Arts programming, which included performance, media, and other forms that came within the range of No Rio’s experimental, interdisciplinary format. During the second Reagan administration No Rio received notice that although the peer panel had recommended funding, Chairman Hodsol requested that the panel reverse their recommendation on the basis of his opinion that the application had demonstrated “a decrease in the quality of work submitted”. Chairman Hodsol recommended a total cut….

It was rare until then for an NEA Chairman to use his veto power. Despite our emphatic requests for an explanation of the aesthetic basis of the NEA’s determination, a critique that would aid us in making subsequent applications, the NEA would not provide details beyond the explanation that the determination was made on the basis of the chairman’s appeal. No Rio researched and discovered cuts were made with similar severity nation-wide. The organizational profiles were similar to No Rio’s: Small, minority based, with direct social or political programming content. The tactic of using “qualitative” arguments to defund organizations predated the time when overt ideological opposition would be sufficient to withdraw government support.

The NEA’s right wing detractors knew that had they been candid about their political agenda from the beginning they [would] have been met with immediate opposition. But because in the beginning, the erosion of public support for the arts affected only small minority organizations, the cross section of arts organizations that No Rio contacted would not or could not see themselves as being on common ground, made no gesture of solidarity and therefore did not reap the possible benefit of immediate mobilization. The right wing’s divide and conquer tactics – predicated on the art world’s indoctrination by precepts of social hierarchy – worked. Only when the funding of recognized artists and the administrative budgets of the more established arts organizations were affected was there a concerted effort to respond. By that time it was too late.

Politics

Archiving the unarchivable becomes even more crucial in light of the ruling class reflex to erase that which threatens it. These tactics are manifold: One is by ignoring the object of dissent; not allowing it access to public venues like the mainstream press. Another is by buying it off, turning radicalism into fashion or product (’60s radical chic or the ‘90s Broadway hit Rent [also a movie, 2005]. Another method is through overt tactics of strangulation for example Mayor Guiliani’s 1999 attempt at closing the Sensation exhibit at the Brooklyn Museum of Art and (ridiculous as it may seem) the arrest of art dealer Mary Boone in the wake of this publicity battle. Embedded in the contiguous philosophy which is the fiber of No Rio’s legacy is an imperative that despite the odds the messages be heard. The inherent condition of limited funding, combined with the ambivalence on the part of the culture at large (including that of the alternative art community); its view of No Rio and its production as marginal, irrelevant, insignificant determined that the archive and the collection be assembled and maintained by innovative adaptations to standard methods.

Availablism

Availablism is a word coined by Israeli performance artist Yuri Katzenstein in 1984. It means making the best possible use of whatever materials are available. Limited resources dictate process, form, and content. Availabism turns simple resourcefulness into an aesthetic. In New York in the ‘80s, artistic and social being were the same thing. Entrepreneurialism was supreme. You could exhibit art work in nightclubs. Massive group shows like the 1000 Balloons show where a thousand balloons containing art made by so many artists were released from the roof of Danceteria. A cheap stunt by all definitions. But the lineup of artists was incredible. Just the volume alone, the diversity, the randomness. Names and titles listed in notes and fliers all packed away in storage. The long forgotten, dead or otherwise gone mixed up with the few remaining survivors.

You could do strange ritualistic performances at Limbo Lounge on 10th and Avenue A. Or a reading at Darinka on Houston. Or caberet at Club Armageddon at the Jane West Hotel. Or a modern ballet at Danceteria on 21st street, or an esoteric performance piece at No Se No or an impromptu post modern dance improv at the SIN Club, which stood for Safety in Numbers meaning you better not go beyond Avenue C alone after dark. ABC No Rio was another place you could go for fun and enlightenment if you could stand the cold, the dirt, and the smell. Often times that meant frankincense, fresh soil, and dry leaves brought inside; the exploding of a pine tree bonfire in the garden in the dead of winter. Art was a state of mind made manifest in constant daily interactions. The line between maker and viewer was often blurred. “No clean hands” Aline Mare of Erotic Psyche used to say. In the ‘90s the pre-cyber post-punk subculture emerged among small communities of squatters, cultural workers, and political activists. ABC No Rio’s Cult X short for CULTural eXchange reflected remaining but threatened elements like Umbrella House, Bullet Space, [the network of] community gardens, Blackout Books, World War III magazine.

Preservation, Value and the Cult of Personality

Another main obstacle in preserving and archiving the work produced at, by, and for ABC No Rio is the fact that much of it has either been collectively produced or concerned with content that does not highlight the individual career of a given artist. Value in western industrial art is charged with the speculation and commodification of the personality of its perceived creator; as if art could possibly be the sole product of a singular effort. The cachet of the personality associated with the product imbues the product with value. Whether the attempt should be made to imbue No Rio and the collectives that have been associated with it with a collective personality, in order to be recognized, remains a question. Such a ploy would be a contradiction of the original intent of groups like Cheap Art, Anti-Utopia, Bullet Space, Sister Serpent, the Purple Institution, and Rehab Video, to name a few. Since the market value of an oeuvre is determined by the comparison of given work’s desirability to a similar work with established value precedent, and that most works in the collection were not oeuvre driven (without the intention of a canonic reference), the market value of the individual works – even those by artists that now have a market presence – is questionable. But so long as the archive remains intact, the archive’s historical, social aesthetic and educational value is enormous….

Afterword – April 2021

Though Yuri Katzenstein was the first person I remember pronouncing the concept of ‘availablism’, Kembra Pfahler has consistently emphasized the idea over the years, making it a fundamental expression of her work. Looking back at my writing I feel freer with the notion that the “coining” of an idea has little, if any relevance to the idea itself. It is interesting looking back at how language changes our relationship to culture and society. In referencing the Culture Wars of the late ’80s into the ’90s I talk about “minority based organizations”, as today the specificity of People Of Color, Black, and African American have stronger and more significant bearing. I’m reminded that among the artists singled out by then Mayor Giuliani in his attack of the Brooklyn Museum’s pivotal exhibition Sensation that the Black Anglo-African artist Chris Ofili’s The Holy Virgin Mary was singled out among the show’s greatest offenses.

When I delivered this paper at the turn of the current century it felt like, with the recession of powerful movements like ACT-UP, the sustained disappearance of an effective black militancy, and the prolonged absence of visible anti war movements – that an era of resistance had indeed forever passed. With the renewal of a war resistance beginning with Afghanistan, the resurgence of large public queer protests agitated by the 1998 murder of Matthew Sheppard, the reawakening of widespread feminist outrage represented by Me Too, and the advent of BLM, it seems at this writing that resistance did not die, it merely went underground. Looking back on my position of a “dying culture of resistance” I’m hopefully heartened that the preservation and exposure of the creative artifacts of these cultures will last as inspiration, example, and proof that, while the collective expression of liberation might appear to be suppressed for sustained periods of time, that the People United Will Never Be Defeated.

Jack Waters and Peter Cramer’s current project is the Petit Versailles garden in Lower East Side, New York City

Colab Collection description

The collection formed around the storage requirements of the MWF Video Club, a Colab project managed by A.W. Moore. It includes 6-800 videotapes, and some analog-era video equipment (VCRs, etc.), display equipment, and many boxes of paper records. (These paper records have been deposited with the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research at the University of Wisconsin, Madison and currently await processing.)

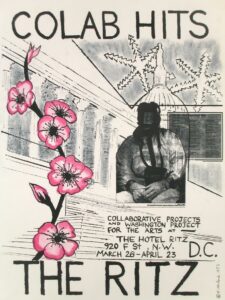

The artworks are mostly from the “Colab Hits the Ritz” show in Washington, D.C. in 1983, and later Colab projects. These include the “Presidential Portraits” series exhibited at the Ritz, multiples store items consigned by artists to the Ritz store, several large artworks from the Ritz show, two 30-foot long collaborative murals, props from the Potato Wolf cable TV series, and sundry items.

Also present is the “Check Show” organized by Sophie Vieille, in its shipping box from its European exhibition; the “Chain Paintings of Love” project of John Morton & Holly Block with nearly 100 artists; and portfolios of flat art material from different Colab projects.

There is also a portion of the ABC No Rio collection held in this space. (Parts of this collection are in the possession of Becky Howland and Marc Miller, since they were dispersed during the preparation of the “Real Estate Show Revisited” exhibition in 2014 and not recovered.)

The storage includes boxes of publications produced by Colab (e.g., ABC No Rio Dinero book), and other publications related to Colab.

There are several boxes of records and slide folders from the Art & Science Collaborations, Inc. (ASCI) from the early 2000s, a project directed by Cynthia Pannucci which were salvaged from the street.

Beckys_variation

ColabhitstheRitz